Introduction to Comparative Studies

Recovering the World Behind the Bible, Part 1

When I first heard the phrase comparative studies in relation to the Bible, it sounded suspicious. I had been trained, in a sense, to view anything “academic” with caution, since so much of the scholarly world seemed to dismiss the Bible’s inspired nature (or at least, I’d heard stories and watched movies like God’s Not Dead). The idea of looking at ancient texts and religions from the nations surrounding Israel felt spiritually dangerous, like I’d be opening a door that might erode my faith (even though the ancient world fascinated me).

I even remember a coworker once trying to convince me that Genesis was just a reworked Egyptian Book of the Dead. As a new Christian, I had no idea what to say. I didn’t know a thing about Egyptian funerary texts, so I stayed quiet (feeling embarrassed) and walked away unsettled, determined to do some research later.

That moment stuck with me, because the fear beneath it (and the embarrassment) was real. I was afraid of losing my faith, though I didn’t want to admit it. And I had such a high opinion of the infallibility of the Bible that I didn’t want to admit that it may not have the answers for every problem or be totally unique and better than other ancient literature.1 These fears turned into a drive to prove that the Bible was “right,” “unique,” or “better,” leading me to study apologetics. However, after being introduced to Dr. Michael S. Heiser’s content, I quickly learned that some of the logic I was using to “prove” the Bible was actually not sound (and sometimes rather ridiculous — like claims that the Bible was older than certain pagan texts — which in many cases it is clearly not — and that older meant “truer”, which is a logical fallacy, that is, chronological snobbery, i.e. appeal to tradition).2

What Comparative Studies Is (and Isn’t)

Comparative study of the Bible began (more or less) in the 19th century when discoveries of Mesopotamian and Egyptian texts led some scholars to argue that Israel simply “borrowed” its stories, a view known as Pan-Babylonianism. This extreme claim was later rejected, and more balanced voices like W. W. Hallo pointed out that considering both similarities and differences between Israel and its neighbors yielded more realistic conclusions.

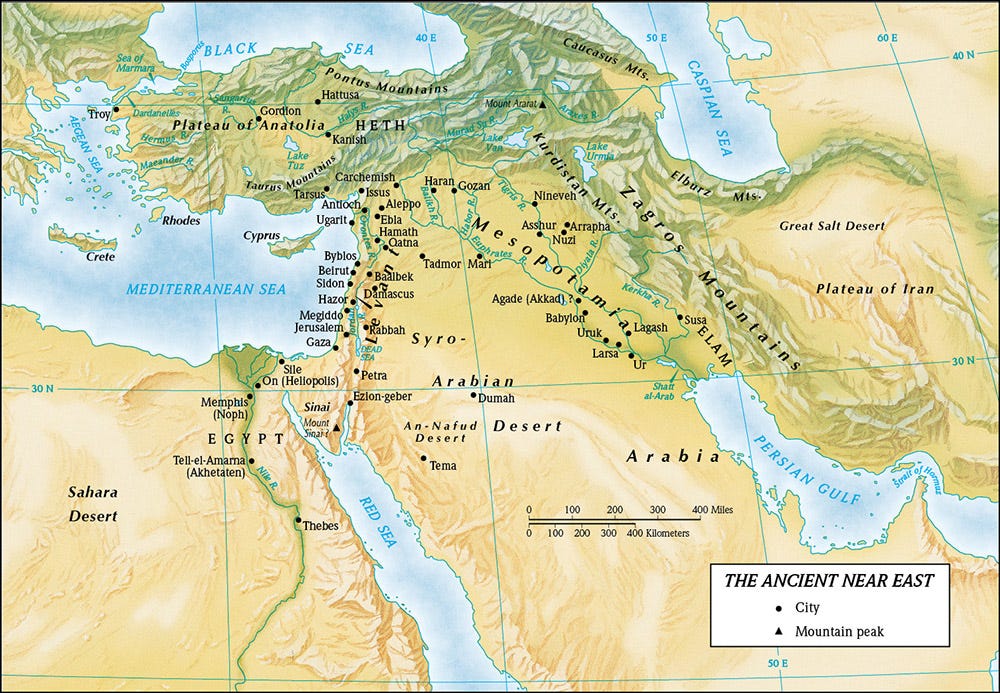

In the 20th century, scholars such as Hermann Gunkel and William F. Albright developed methods that highlighted Israel’s shared cultural world while also noting its distinct theology. Today, following voices like John Walton and Michael Heiser, comparative studies are understood not as a way to undermine the Bible but as a tool for recovering the ancient cognitive environment3 in which it was written. This results in helping modern readers grasp its meaning in its own world before applying it to ours.

This is why Heiser’s content was such a breakthrough for me. By way of Walton, Heiser made the case that comparative study is not about disproving the Bible. While some have used it that way, many biblical scholars now use it to recover the world the Bible came from, that is, the ideas, symbols, and categories its first hearers would have instantly recognized, but we often miss.

In his book Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament, Walton writes that the Bible was not delivered in a cultural vacuum. God chose to reveal himself in a particular time, place, and world — the ancient Near East. That means Israel’s Scriptures use the language and worldviews of that time, even while often reframing them to declare something radically different about God.

Comparative study, then, isn’t about showing the Bible is “just like other ancient myths.” It’s about seeing both the shared language and the unique claims.

Why This Matters

If we forget that the Bible was written for us but not to us (a concept I will discuss in subsequent posts), we risk flattening it into our own cultural categories. That leads to things like:

Misapplied commands — treating Israel’s ancient laws as if they were aimed directly at modern Christians.

Distorted theology — reading Hebrew words as though their English equivalents capture the full meaning (Hebrew words often convey concepts and rich contextual meaning).

Shallow faith — reducing concepts like covenant loyalty to modern “niceness” or “positivity.”

Confusion and doubt — when the Bible feels “weird” or contradictory because we expect it to speak in our categories.

If we want to know what the Bible means, we first have to know what it meant.

A First Glimpse at the Principles

In this blog series, I’ll explore some guiding principles that flow out of comparative study (many of which come from the work of scholars like John Walton and Michael Heiser). For now, here are a few to set the stage:

The Bible Was Written for Us but Not to Us4

God’s Word speaks to every generation, but it was first addressed to ancient peoples in their own context.Meaning Resides in the Ancient Context

The message of Scripture emerges from the world of its first audience. We can’t shortcut that step.Parallels Don’t Equal Dependence

Similarities to surrounding cultures don’t prove copying. They show Israel lived in the same world, and sometimes God used that world as the backdrop for His revelation.The Bible Engages Its World

Sometimes it agrees with the views of neighboring cultures, sometimes it criticizes and sometimes it radically redefines, but it always speaks in terms the original audience would have understood.

Closing Thought

Think of comparative study like learning a new language. The more we enter the thought-world of the Bible’s first hearers, the more Scripture expands and becomes richer, stranger, and more alive.

This series is part of the work I’m beginning with Sanctum Priscae Fidei — a new project dedicated to exploring Scripture through ancient Near Eastern comparative studies. The goal isn’t to water down the Bible but to recover its world and its meaning as the original hearers would have understood it. By seeing Israel in conversation with cultures like Egypt, Babylon, and Canaan, we begin to hear the Bible more clearly as God’s Word spoken in the language of its time, yet carrying truth for all time.

Further Reading

Walton, John H. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. 2nd edition. Baker Academic, 2018.

Heiser, Michael S. The Bible Unfiltered: Approaching Scripture on Its Own Terms. Lexham Press, 2017.

Hindson, Ed, and Gary Yates, eds. The Essence of the Old Testament: A Survey. B&H Publishing Group, 2012.

Andrews, Carol, J. Daniel Gunther, and James Wasserman. The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by DayThe Complete Papyrus of Ani Featuring Integrated Text and Full-Color Images. Translated by Dr Raymond Faulkner and Ogden Goelet. Chronicle Books, 2015.

I think that a lot of this pride came form listening to well meaning pastors who were uniformed about ancient history and literature. In their love for God they may have made some prideful uninformed comments and I fell for it. That’s not to say that we should not be proud of our Bible and our God — but we should also remain humble and teachable. There is a lot we as believers can learn from the secular world. And learning from unbelievers or even those hostile to the faith doesn’t mean we are betraying our God. It means we are wise and humble.

I linked to Heiser’s official website, which is currently being reworked after his passing. The best way to get started with his content is to read his books, join his (now free) school AWKNG School of Theology, or just search him up on YouTube. Another great resource is his podcast, The Naked Bible Podcast, which has had a great run over many years. I recommend starting at the beginning and listening through the entire thing.

More on what this means exactly in future posts.

John Walton seems to have made this phrase popular.